The Birth of the Quonset Hut, A Spiritual Carpenter’s View

Key Takeaways

- The Quonset hut, first developed near Quonset, Rhode Island during WWII, became a symbol of durable and efficient military architecture that blended functionality with nature-inspired design.

- Built with an

arched, clam-shell structure, the Quonset hut’s curved form offered superior strength and wind resistance—ideal for extreme environments like Greenland’s icy conditions.

- Larry Haun’s personal experience as a Navy Seabee revealed the hut’s practicality and spiritual resonance, showing how purposeful design can connect humans more closely with nature.

- His reflections in Greenland highlighted the

environmental impact of human activity, emphasizing the importance of mindful construction and minimal pollution.

- The story reminds us that

simplicity, adaptability, and respect for nature are enduring lessons from the Quonset hut’s legacy and Haun’s journey as a “spiritual carpenter.”

In honor of Veteran’s Day and the 1 year anniversary of our Boathouse, we thought it appropriate to honor both our service men and women and our Boathouse’s history.

Adapted from Larry Haun’s (1931-2011) blog, A Carpenter’s View:

“My Story: The Quonset Hut”

“ I want to do with you what the spring does to the cherry tree.

”

–Pablo Neruda

Does anyone still remember the Korean War? Or is it just another forgotten war that happened elsewhere some 60 years ago? Even a causal reading of history shows that the list of our forgotten wars is long, long. To my surprise, this deadly war opened me somewhat like a cherry blossom.

The Quonset hut was born in one of our many wars. In many ways this hut is an icon of WWII especially in the Pacific war theater. Yes, that’s what they call it–theater. The problem of housing the huge number of military personal along with storing materials needed to wage a massive war was vast. Today, that same spirit of teamwork and engineering can be seen in modern projects, from bridges to guided white water rafting expeditions that test both strength and collaboration. Inventive minds quickly found a solution and started producing this oval, metal building near Quonset, Rhode Island, from whence comes its name.

Sometimes we get things right and build like nature does. There is a natural way of being that seems to be unknown or simply ignored by us. We build our houses in straight and square lines. Where do we see this in nature? The Quonset hut is an exception. This strong, stable, half-round structure is shaped like a clam shell, the long-house of the Iroquois People, or the curved home a turtle carries around on its back. Its natural curves remind us of the geological wonder carved by rivers like the Snake River in Hells Canyon.

I was a journeyman carpenter so I joined a reserve unit of Navy Seabees, a construction battalion (much like how small groups join our special interest rafting trips today, each member bringing a unique skill to the adventure). It wasn’t long after that, in Oct. 1951, that I was called up for two years of active duty. I was sent to boot camp at the large naval base in San Diego and trained in the art of war.

From San Diego, I went to Port Hueneme, north of Los Angeles, for further training in construction. It was at this base that I encountered rows of the versatile Quonset hut set up for hundreds of different uses. I lived there in a hut for three months. This base is a training and staging area for military construction workers being prepared to build and fight in a war zone. I was there with a battalion of young men, more than seven hundred of us, all scheduled to be sent to Korea.

Maybe someone can help me understand what came next. It happened near the end of our training. We were preparing our gear to ship out to the Korean Peninsula when I was approached by an officer I had never seen and did not know. He came up to me with one question: “Do you want to go to Korea?” I answered—well, no, not really. He turned and left. I and one other recruit from Indiana, received orders to report to the Seabee base in Quonset Point, Rhode Island! Everyone else was headed for the war zone. I’m serious, what was going on here?

Quonset Point, the home of the Quonset hut. There I was placed in another battalion and we were soon on our way to Newfoundland, an island province off the coast of eastern Canada, to build landing strips and a new base post office.

The six months in Newfoundland passed quickly and we returned to Rhode Island. That rhythm of seasons and travel reminds us of the steady pace of rivers like the Grande Ronde—quiet stretches punctuated by moments of excitement. Again it happened.

Shortly before we were ready to leave for Cuba, another officer came to me. He said that there was a special group that had been undergoing survival training in Canada and were preparing to leave shortly for an experimental task on the Greenland icecap. The carpenter who was part of this small group had an appendectomy and wouldn’t be going on this expedition. Would I be willing to take his place?

The fringe benefits of growing up in Nebraska: Maybe he asked me because my records showed that I came from western Nebraska where winters can be almost as bad as those in Greenland. I said yes. The nine member group I joined had three mechanics, an electrician, a cook, two equipment operators, an officer, and me the carpenter.

It was called the US Navy Seabee Hardtop Detachment and left for Greenland around Christmas time, 1952. Greenland is the world’s largest island about three times the size of Texas. The Greenlanders have home rule, but the island is still owned by Denmark and is mainly covered by a thick, now rapidly melting, ice sheet.

We arrived at Thule air force base located on the west coast of Greenland about half way between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole. We stayed at the airbase for a time, preparing to set up our camp about thirty miles out on the icecap. Our project was to see if the nine of us could use heavy equipment to build an airstrip on the ice that would support the landing of wheeled aircraft.

Four of us were transported out to our station on the ice cap. Besides us, the plane carried basic supplies, two tents, small stoves, fuel, food, and bedding to begin camp setup. We landed, looked around, unloaded our gear, and began to set up our tents. We cut blocks of ice-snow to form a wind barricade and a place for our toilet, had some food and crawled into our sleeping bags.

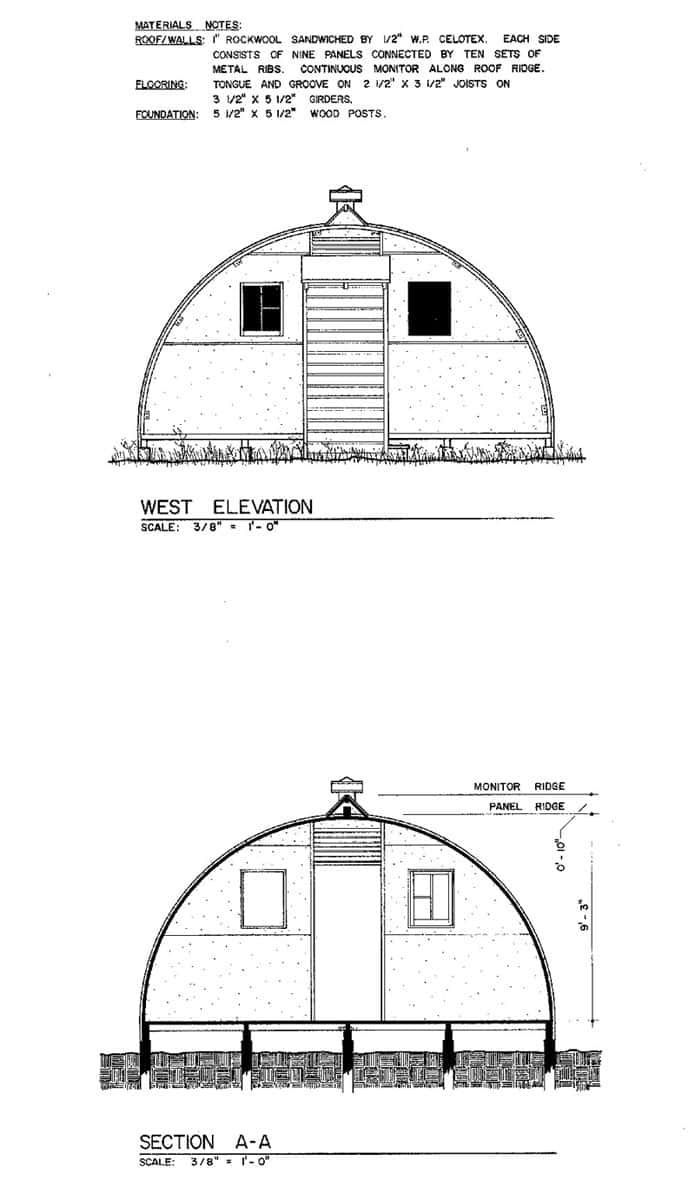

The two Jamesway huts, each 16 ft. x 16 ft., came in 1,200 pound packages. We opened the boxes and set them on the 2×12 foundation bolting them together to make the floor. The ribs were made from wood and joined together to form an arch. Each arch was attached at each end to the floor by a bolt. Each arch was attached to the next one by a spacer that hooked the two together. Once we had all the arches in place, we began covering them with the insulated blankets that measured 4 ft. wide. These blankets attached to the ribs, to each other, and to the floor to keep them in place. The ends of the hut were also covered with insulated blankets that had a vent for air circulation and an entry door. We had practiced putting them together back at the airbase so even though we were working in -0 degree weather, we had the first hut in place in less than three hours. When you are in the middle of Greenland, you may not have the luxury of building slow.

In less than a week we had the two huts in place along with stoves for heating, cooking, and melting ice to use as drinking water. Our two small stoves, burning diesel fuel, made me realize how little it takes to pollute our environment. Within a short time, the endless snow and ice around our living space was coated with black soot. It helped me to understand the impact a million gas burning cars and hundreds of coal fired plants generating electricity has on the quality of air we breathe in our cities and throughout our country. City folk must have lungs the color of the blackened snow.

Rounded buildings work much better in this cold, windy climate than those with a flat side like a regular house. Nature always finds efficient shapes—just as the Salmon River carves elegant curves through Idaho’s rugged wilderness. The wind blows up and over their tops. Once all our buildings were complete we were quite warm and cozy. It wasn’t long before our home was further insulated by snow and ice particles that drifted over the huts.

We staked out an airstrip less than a mile away and began work. We organized ourselves, working 4 hours on and 4 hours off, keeping at the airstrip building task 24 hours a day, seven days a week. We seldom shut the engines off on our two small caterpillars. We used the Cats to pull an ice pulverizing machine up and down the landing strip breaking the ice into smaller and smaller particles and then compacting all with a heavy roller. Hard work, but at least I wasn’t expected to kill Koreans. For that I am forever grateful.

We had instruments to test the depth and degree of hardness of the airstrip to see if it would support a wheel landing of a C-47. Once the desired hardness was reached, we radioed the pilot at Thule airbase to give it a try. He arrived in an unloaded plane and safely landed, took off, and landed again on wheels rather than skis without incident. I guess we, like our former president, could say: “Mission accomplished.”

The dangers that we met in that frozen part of the world helped me to see that we are part of nature not its master. Life there was one of survival unencumbered by a truckload of things that clutter our lives and keep us from being who we really are. And who are we really? I remember what an woman told me once: “I am just an old woman trying to live simply and be loving toward myself and others.”

All paths, in the end, lead to the same graveyard. Living in the far north taught me to follow a path that allowed me to wake up, be present and in touch with my heart. Please tell me, what else is there in life?

To learn more about Larry’s interesting life, the New York Times wrote a great piece on him before he died in 2011. The Carpenter’s Carpenter.

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore the fascinating story behind the Quonset hut — a wartime invention that became a symbol of resilience, ingenuity, and simplicity, as told through the reflections of master carpenter Larry Haun.

What is a Quonset hut?

A Quonset hut is a lightweight, semi-circular metal structure originally developed during World War II to house military personnel and store equipment. Its design, inspired by natural forms, makes it durable, easy to assemble, and highly adaptable for various uses — from barracks to workshops.

Where did the Quonset hut get its name?

The Quonset hut was named after Quonset Point, Rhode Island, where it was first manufactured for the U.S. Navy in 1941. The location became synonymous with this practical, portable building that would later be shipped around the world during wartime.

Why were Quonset huts so popular during World War II?

Quonset huts became essential during WWII because they were fast to produce, easy to transport, and could be assembled by untrained soldiers. Their curved design provided strength and efficient use of materials, helping meet the urgent housing needs of troops in remote locations.

How is the Quonset hut connected to the Korean War?

Although first used in WWII, Quonset huts continued to serve through the Korean War as versatile, reliable structures for soldiers. In Larry Haun’s story, they also represent a personal turning point — a symbol of shelter, reflection, and survival during his Seabee service years.

What makes the Quonset hut design special?

Its half-round, arched design mimics natural shapes like clamshells and turtle shells, allowing wind and snow to flow over it easily. This curvature gives it both strength and stability — making it ideal for extreme climates like Greenland, where Larry Haun built them on the ice.

How were Quonset huts assembled?

Quonset huts were built using prefabricated metal ribs bolted to a simple wooden floor and covered with insulated panels or metal sheets. Even in freezing conditions, crews could erect one in just a few hours, providing instant shelter in harsh environments.

What was Larry Haun’s role in building Quonset huts?

As a Navy Seabee carpenter, Larry Haun helped construct Quonset and Jamesway huts during his service in Greenland in the early 1950s. His work involved building insulated shelters and airstrips on the icecap — an experience that deepened his respect for simplicity and nature’s design.

How did Larry Haun’s experience shape his philosophy?

His time in the Arctic taught him that humans are part of nature, not above it. Living simply, working cooperatively, and respecting natural forms became central to his outlook as a “spiritual carpenter” — guiding his craft and life philosophy.

What did Larry Haun mean by “building like nature does”?

Haun believed that good construction should harmonize with natural forms rather than fight them. Unlike boxy buildings, the Quonset hut’s rounded design reflects nature’s efficiency and beauty — reminding builders to follow organic principles in their work.

How did this experience change Larry Haun’s view of life?

Working in isolation on the Greenland icecap made Haun realize the importance of simplicity, presence, and compassion. Stripped of distractions, he found that life’s essence lies in awareness, love, and connection — not possessions or power.

Why is the Quonset hut still significant today?

Beyond its military origins, the Quonset hut remains a symbol of adaptability and sustainable design. It continues to inspire architects, builders, and craftspeople as a model of efficiency, resilience, and the beauty of simple, functional construction.

The post The Birth of the Quonset Hut, A Spiritual Carpenter’s View appeared first on Winding Waters River Expeditions.